Hyperfocal distance is a concept in landscape photography for achieving as much sharpness as possible throughout the image. In other words, it involves careful focusing adjustments to ensure that objects close to the camera and objects in the distance all have the same sharpness. More accurately, the hyperfocal distance is that point of focus where things are sharp from a point half way between you and the focal point all the way onward to infinity.

When I am composing landscape photos, I never use auto-focus because this could interfere with some important focal point decisions. My 24mm prime Canon lens has visual markings to show you the distance to the focal point. Many digital lenses don’t have markings for focus as they are all digital. For these lenses, I recommend using live view to fine-tune your focal point.

You could use auto-focus to set your focal point if an object is at the correct hyperfocal distance. If you have a touch-screen live view, you can fix your focus appropriately. If you instruct your auto-focus system to focus on the lower 3rd intersection, then you will be close to the hyperfocal distance, and this will be fine in 95% of your nature photography.

Circle of confusion

Although the Hyperfocal distance can be stated mathematically as an exact adjustment, lenses are rarely perfect and are likely to vary in different temperatures. Also, we have the concept of ‘acceptable sharpness’, which is related to the ‘Circle of Confusion’. The circle of confusion is the point at which a pixel in a digital image goes from being a dash (sharp) to a circle (un-sharp). If your DOF doesn’t cover the whole scene, then the circle of confusion will set in at some point in your image.

Private Northern Lights Tours

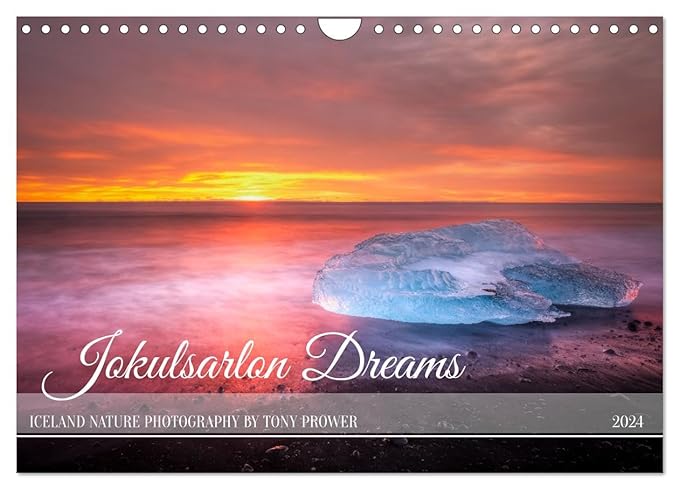

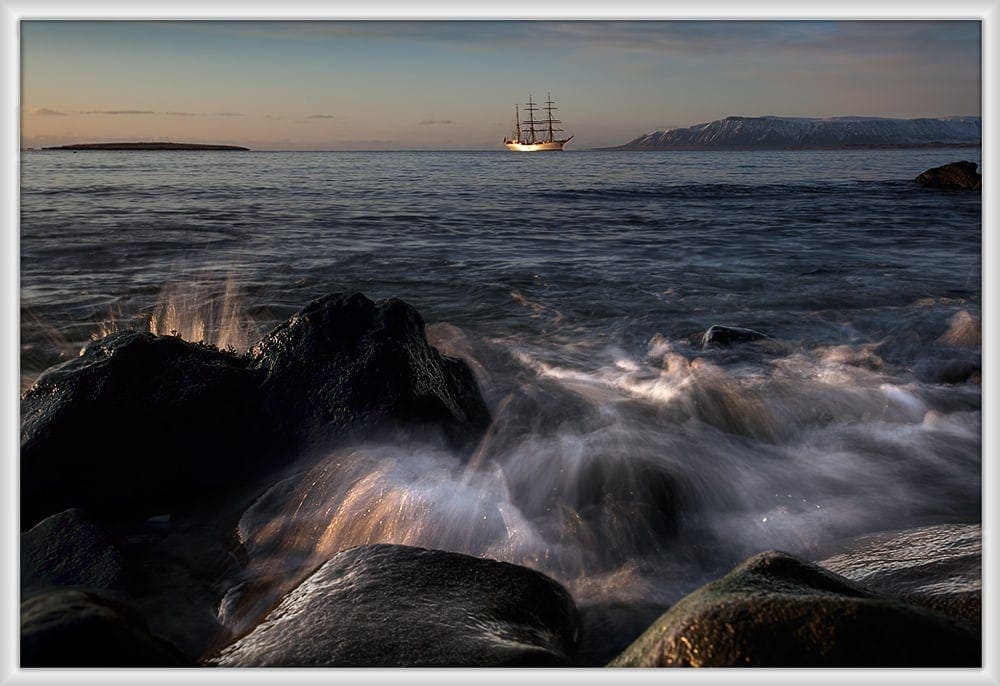

Out to Sea

The above image has interest points in the immediate foreground and also on the horizon, so hyperfocal distance was important for this shot. However, even at f/16, the distant ship and the foreground rocks are only just acceptably sharp. The hyperfocal distance for this image is out in the sea. In my opinion, it would have been better to take a shot focusing on infinity and then a shot focusing on the rocks and blending them together (see here). The sea is the part of the image with the best focus, and yet it doesn’t really matter if this is sharp or not.

Lens: Sweet Spot

The perfect lens doesn’t exist, although there are some very good ones. Typically, lenses become soft as you deviate from the sweet spot (best aperture for sharpness). The sweet spot is often in the middle of the lens’s aperture range, say around f/8, but some say that it is 2 stops down from fully open. So we might stop down to f/16 or f/22 to achieve a greater depth of field. We would hope for sharpness throughout the image, but because we have deviated so far from the sweet spot, we are not really getting the best sharpness from the lens.

Ultimately, it becomes a trade off. Whatever aperture you decide to use for a large landscape DOF will either sacrifice the lenses potential for DOF or Sharpness. All we can really say, with really large apertures, is that near objects are as sharp as distant objects. Lenses often degrade in quality as you deviate from the centre apertures. My compromise for landscape photography at 24mm was f/11. From a reasonable tripod height, there is no reason not to have acceptable sharpness throughout the scene.

Acceptable sharpness comes into play when we consider how an image is going to be viewed. For example, reducing an image for the web will increase the apparent sharpness, whereas printing it large will have the opposite effect. Consider objects on the horizon. If you calculate the hyperfocal distance accurately, you should have perfectly sharp objects on the horizon. But, if those objects are just a few pixels across, then there is little point in achieving this absolute sharpness.

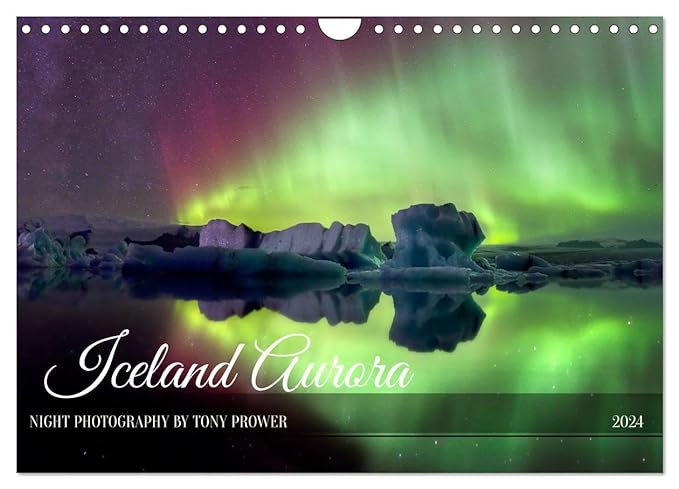

Infinity Focus

The above night photograph was focused just short of infinity, leaving the foreground boulders fairly out of focus. As it was night, I couldn’t use a small aperture without incredibly long exposures. This was taken at f/5.6. For me, the importance was the lights in the distance. There was no way I was going to get a balanced exposure with good detail of the boulders, so I chose to have them as un-sharp masses; they just add to the depth, but their sharpness isn’t important.

Rule of thumb

In the days of 35mm film, lenses used to be pre-marked with hyperfocal information. For example if you were using f/11 aperture, there would be a mark on your lens where you aligned the infinity sign to f/11 and this would give you the hyperfocal distance. For some reason this is missing on many modern digital lenses, although I do have hyperfocal marks on my Canon 24mm 1.4L. I use these markings more than anything else for focusing a landscape scene.

If you don’t have the markings on your lens and you want a quick rule of thumb to give a rough hyperfocal distance, simply focus a third of the way into the scene.

Ok, so if you are still reading this, you may have a near-perfect lens and a huge mega-pixel camera, and so the achievement of absolute sharpness does matter. I recommend browsing the technical pages using the following links:.

www.dofmaster.com

www.trenholm.org